Moving beyond perfect

Perfection is problematic. Robin Henderson, Managing Director of MY Consultants and AHUA Development Consultant, shares his views on the risks of seeking perfection. Moving forward, failing fast, and learning from our experiments is a more empowering use of our time.

I have sat here with a blank page for the last few days thinking about the topic for my first development blog. I have been trying to work out which of the multiple topics would be perfect to kick the series off.

Of course, the self-evident answer is that there is no perfect topic, just several potential topics which will resonate differently for different readers.

For me, this raises questions linked to resilience, change, and decision-making. We should let go of the search for the “perfect answer” and value the process of experimentation and learning – both as individuals and organisations.

This seems even more important now, as the level of uncertainty created by the pandemic and Brexit aren’t abating. The search for the way forward remains an even more complex task.

At an individual level, the desire for perfection comes at a price:

- long working hours

- an unwillingness to delegate, as the quality may not be as good as if you had done it yourself

- not completing complex tasks where assessing quality may be challenging

- frustration when mistakes are made

- anxiety about how your work might be evaluated by others.

If you recognise this behaviour in yourself, it is worth being actively conscious of it. Regularly ask questions such as:

- What tasks are you not undertaking because you are trying to do everything to a very high standard?

- How might these tasks which are not happening impact your long-term performance, and the organisation’s?

- How might this behaviour impact on how your team feels about trust within the workplace?

What are the impacts of this behaviour beyond the workplace? - Which activities could you do slightly less well without compromising key decisions which you or others make?

At an organisational level, the desire to be perfect can lead to stagnation and in-action.

During the pandemic, I can vividly remember working with many groups transitioning teaching online. They were searching for the correct answer, when there clearly was no best solution.

This was sometimes exacerbated by leadership teams who did not want to make decisions, as they wanted to maintain academic autonomy, or did not have enough knowledge to make effective decisions.

This desire to make correct decisions really impacted people’s ability to deliver – and as result their resilience, stress, anxiety, and sense of competence.

So how can you move past this need for the correct answer?

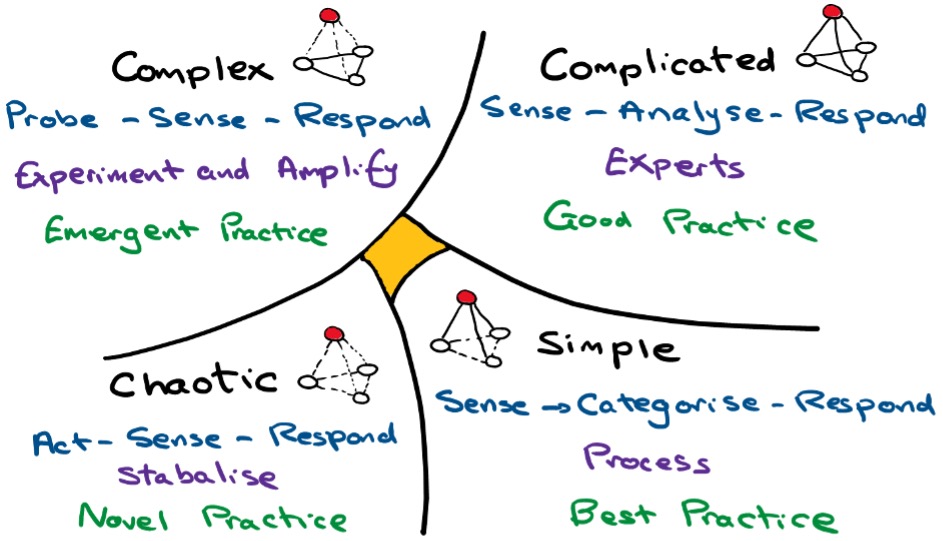

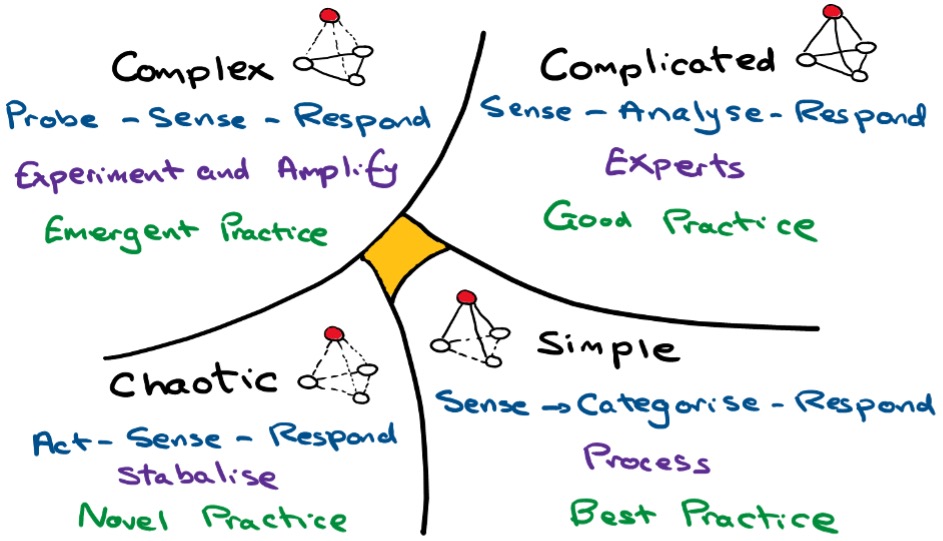

There are several approaches to explore, but one that I find consistently helpful is the CYNEFIN framework developed by David Snowden.

Within the framework he identifies four habitats:

- A simple habitat where solutions are clear and best practice exists. In this space traditional approaches to management will yield good results

- A complicated space where good practice exists and bringing together experts should allow identification of effective solutions.

- A chaotic space where there is no right or wrong answer and what is required is action to stabilise the organisation.

- Finally, there is the complex space where there is no correct answer and often many routes forward.

Image: The CYNEFIN Framework

Many of the issues we face in higher education occupy the complex space.

These include the return to campus, the move to blended approaches to learning and teaching, and the changing nature of internationalisation.

Given this complexity, you will need to be more conscious of how you adapt your leadership to this context. Specific approaches include:

- Ensuring that you don’t oversimplify complex situations, leading to unanticipated knock-on impacts. An example of perceived oversimplification has been COVID mitigation policies in many higher education institutions. This has led to challenges for staff to manage workloads and find time for a meaningful holiday – especially around extension of the assessment and feedback process.

- Noticing when the discussions become loops and revisit the same old arguments. If this is consistently occurring, then it is likely that there is no “perfect solution.” Your task as a leader is to create a space where individuals feel empowered to act, even when there is a risk of failure.

- Recognising the value of experimenting. Test outcomes quickly rather than over-deliberating on what the correct answer should be. Where the experiment is not working, move quickly to the next approach. Effectively, test outcomes frequently and fail fast. Where the experiments yield positive results, amplify the approach across the organisation by sharing successes and enabling wider action.

- Moving to non-traditional approaches to project management. For example, try “Agile” project management. Operate in short sprints of activity before testing outcomes, and then design the next sprint of activity.

At the heart of leadership in this space is creation of a culture where complexity is embraced. Empower individuals and teams to aim to move forward, rather than aiming for the perfect answer. Encourage them to learn and share in order to enable organisation-wide collective action.

If you would like to explore this topic in greater detail have a look at:

Robin Henderson is the AHUA Development Consultant and the Managing Director of MY Consulting.

Related Blogs